- Home

- E. M. Forster

Works of E M Forster Page 14

Works of E M Forster Read online

Page 14

Harriet, however, talked little. She had seen enough to know that her brother had failed again, and with unwonted dignity she accepted the situation. She did her packing, she wrote up her diary, she made a brown paper cover for the new Baedeker. Philip, finding her so amenable, tried to discuss their future plans. But she only said that they would sleep in Florence, and told him to telegraph for rooms. They had supper alone. Miss Abbott did not come down. The landlady told them that Signor Carella had called on Miss Abbott to say good-bye, but she, though in, had not been able to see him. She also told them that it had begun to rain. Harriet sighed, but indicated to her brother that he was not responsible.

The carriages came round at a quarter past eight. It was not raining much, but the night was extraordinarily dark, and one of the drivers wanted to go slowly to the station. Miss Abbott came down and said that she was ready, and would start at once.

“Yes, do,” said Philip, who was standing in the hall. “Now that we have quarrelled we scarcely want to travel in procession all the way down the hill. Well, good-bye; it’s all over at last; another scene in my pageant has shifted.”

“Good-bye; it’s been a great pleasure to see you. I hope that won’t shift, at all events.” She gripped his hand.

“You sound despondent,” he said, laughing. “Don’t forget that you return victorious.”

“I suppose I do,” she replied, more despondently than ever, and got into the carriage. He concluded that she was thinking of her reception at Sawston, whither her fame would doubtless precede her. Whatever would Mrs. Herriton do? She could make things quite unpleasant when she thought it right. She might think it right to be silent, but then there was Harriet. Who would bridle Harriet’s tongue? Between the two of them Miss Abbott was bound to have a bad time. Her reputation, both for consistency and for moral enthusiasm, would be lost for ever.

“It’s hard luck on her,” he thought. “She is a good person. I must do for her anything I can.” Their intimacy had been very rapid, but he too hoped that it would not shift. He believed that he understood her, and that she, by now, had seen the worst of him. What if after a long time — if after all — he flushed like a boy as he looked after her carriage.

He went into the dining-room to look for Harriet. Harriet was not to be found. Her bedroom, too, was empty. All that was left of her was the purple prayer-book which lay open on the bed. Philip took it up aimlessly, and saw— “Blessed be the Lord my God who teacheth my hands to war and my fingers to fight.” He put the book in his pocket, and began to brood over more profitable themes.

Santa Deodata gave out half past eight. All the luggage was on, and still Harriet had not appeared. “Depend upon it,” said the landlady, “she has gone to Signor Carella’s to say good-bye to her little nephew.” Philip did not think it likely. They shouted all over the house and still there was no Harriet. He began to be uneasy. He was helpless without Miss Abbott; her grave, kind face had cheered him wonderfully, even when it looked displeased. Monteriano was sad without her; the rain was thickening; the scraps of Donizetti floated tunelessly out of the wineshops, and of the great tower opposite he could only see the base, fresh papered with the advertisements of quacks.

A man came up the street with a note. Philip read, “Start at once. Pick me up outside the gate. Pay the bearer. H. H.”

“Did the lady give you this note?” he cried.

The man was unintelligible.

“Speak up!” exclaimed Philip. “Who gave it you — and where?”

Nothing but horrible sighings and bubblings came out of the man.

“Be patient with him,” said the driver, turning round on the box. “It is the poor idiot.” And the landlady came out of the hotel and echoed “The poor idiot. He cannot speak. He takes messages for us all.”

Philip then saw that the messenger was a ghastly creature, quite bald, with trickling eyes and grey twitching nose. In another country he would have been shut up; here he was accepted as a public institution, and part of Nature’s scheme.

“Ugh!” shuddered the Englishman. “Signora padrona, find out from him; this note is from my sister. What does it mean? Where did he see her?”

“It is no good,” said the landlady. “He understands everything but he can explain nothing.”

“He has visions of the saints,” said the man who drove the cab.

“But my sister — where has she gone? How has she met him?”

“She has gone for a walk,” asserted the landlady. It was a nasty evening, but she was beginning to understand the English. “She has gone for a walk — perhaps to wish good-bye to her little nephew. Preferring to come back another way, she has sent you this note by the poor idiot and is waiting for you outside the Siena gate. Many of my guests do this.”

There was nothing to do but to obey the message. He shook hands with the landlady, gave the messenger a nickel piece, and drove away. After a dozen yards the carriage stopped. The poor idiot was running and whimpering behind.

“Go on,” cried Philip. “I have paid him plenty.”

A horrible hand pushed three soldi into his lap. It was part of the idiot’s malady only to receive what was just for his services. This was the change out of the nickel piece.

“Go on!” shouted Philip, and flung the money into the road. He was frightened at the episode; the whole of life had become unreal. It was a relief to be out of the Siena gate. They drew up for a moment on the terrace. But there was no sign of Harriet. The driver called to the Dogana men. But they had seen no English lady pass.

“What am I to do?” he cried; “it is not like the lady to be late. We shall miss the train.”

“Let us drive slowly,” said the driver, “and you shall call her by name as we go.”

So they started down into the night, Philip calling “Harriet! Harriet! Harriet!” And there she was, waiting for them in the wet, at the first turn of the zigzag.

“Harriet, why don’t you answer?”

“I heard you coming,” said she, and got quickly in. Not till then did he see that she carried a bundle.

“What’s that?”

“Hush— “

“Whatever is that?”

“Hush — sleeping.”

Harriet had succeeded where Miss Abbott and Philip had failed. It was the baby.

She would not let him talk. The baby, she repeated, was asleep, and she put up an umbrella to shield it and her from the rain. He should hear all later, so he had to conjecture the course of the wonderful interview — an interview between the South pole and the North. It was quite easy to conjecture: Gino crumpling up suddenly before the intense conviction of Harriet; being told, perhaps, to his face that he was a villain; yielding his only son perhaps for money, perhaps for nothing. “Poor Gino,” he thought. “He’s no greater than I am, after all.”

Then he thought of Miss Abbott, whose carriage must be descending the darkness some mile or two below them, and his easy self-accusation failed. She, too, had conviction; he had felt its force; he would feel it again when she knew this day’s sombre and unexpected close.

“You have been pretty secret,” he said; “you might tell me a little now. What do we pay for him? All we’ve got?”

“Hush!” answered Harriet, and dandled the bundle laboriously, like some bony prophetess — Judith, or Deborah, or Jael. He had last seen the baby sprawling on the knees of Miss Abbott, shining and naked, with twenty miles of view behind him, and his father kneeling by his feet. And that remembrance, together with Harriet, and the darkness, and the poor idiot, and the silent rain, filled him with sorrow and with the expectation of sorrow to come.

Monteriano had long disappeared, and he could see nothing but the occasional wet stem of an olive, which their lamp illumined as they passed it. They travelled quickly, for this driver did not care how fast he went to the station, and would dash down each incline and scuttle perilously round the curves.

“Look here, Harriet,” he said at last, “I feel bad; I wan

t to see the baby.”

“Hush!”

“I don’t mind if I do wake him up. I want to see him. I’ve as much right in him as you.”

Harriet gave in. But it was too dark for him to see the child’s face. “Wait a minute,” he whispered, and before she could stop him he had lit a match under the shelter of her umbrella. “But he’s awake!” he exclaimed. The match went out.

“Good ickle quiet boysey, then.”

Philip winced. “His face, do you know, struck me as all wrong.”

“All wrong?”

“All puckered queerly.”

“Of course — with the shadows — you couldn’t see him.”

“Well, hold him up again.” She did so. He lit another match. It went out quickly, but not before he had seen that the baby was crying.

“Nonsense,” said Harriet sharply. “We should hear him if he cried.”

“No, he’s crying hard; I thought so before, and I’m certain now.”

Harriet touched the child’s face. It was bathed in tears. “Oh, the night air, I suppose,” she said, “or perhaps the wet of the rain.”

“I say, you haven’t hurt it, or held it the wrong way, or anything; it is too uncanny — crying and no noise. Why didn’t you get Perfetta to carry it to the hotel instead of muddling with the messenger? It’s a marvel he understood about the note.”

“Oh, he understands.” And he could feel her shudder. “He tried to carry the baby— “

“But why not Gino or Perfetta?”

“Philip, don’t talk. Must I say it again? Don’t talk. The baby wants to sleep.” She crooned harshly as they descended, and now and then she wiped up the tears which welled inexhaustibly from the little eyes. Philip looked away, winking at times himself. It was as if they were travelling with the whole world’s sorrow, as if all the mystery, all the persistency of woe were gathered to a single fount. The roads were now coated with mud, and the carriage went more quietly but not less swiftly, sliding by long zigzags into the night. He knew the landmarks pretty well: here was the crossroad to Poggibonsi; and the last view of Monteriano, if they had light, would be from here. Soon they ought to come to that little wood where violets were so plentiful in spring. He wished the weather had not changed; it was not cold, but the air was extraordinarily damp. It could not be good for the child.

“I suppose he breathes, and all that sort of thing?” he said.

“Of course,” said Harriet, in an angry whisper. “You’ve started him again. I’m certain he was asleep. I do wish you wouldn’t talk; it makes me so nervous.”

“I’m nervous too. I wish he’d scream. It’s too uncanny. Poor Gino! I’m terribly sorry for Gino.”

“Are you?”

“Because he’s weak — like most of us. He doesn’t know what he wants. He doesn’t grip on to life. But I like that man, and I’m sorry for him.”

Naturally enough she made no answer.

“You despise him, Harriet, and you despise me. But you do us no good by it. We fools want some one to set us on our feet. Suppose a really decent woman had set up Gino — I believe Caroline Abbott might have done it — mightn’t he have been another man?”

“Philip,” she interrupted, with an attempt at nonchalance, “do you happen to have those matches handy? We might as well look at the baby again if you have.”

The first match blew out immediately. So did the second. He suggested that they should stop the carriage and borrow the lamp from the driver.

“Oh, I don’t want all that bother. Try again.”

They entered the little wood as he tried to strike the third match. At last it caught. Harriet poised the umbrella rightly, and for a full quarter minute they contemplated the face that trembled in the light of the trembling flame. Then there was a shout and a crash. They were lying in the mud in darkness. The carriage had overturned.

Philip was a good deal hurt. He sat up and rocked himself to and fro, holding his arm. He could just make out the outline of the carriage above him, and the outlines of the carriage cushions and of their luggage upon the grey road. The accident had taken place in the wood, where it was even darker than in the open.

“Are you all right?” he managed to say. Harriet was screaming, the horse was kicking, the driver was cursing some other man.

Harriet’s screams became coherent. “The baby — the baby — it slipped — it’s gone from my arms — I stole it!”

“God help me!” said Philip. A cold circle came round his mouth, and, he fainted.

When he recovered it was still the same confusion. The horse was kicking, the baby had not been found, and Harriet still screamed like a maniac, “I stole it! I stole it! I stole it! It slipped out of my arms!”

“Keep still!” he commanded the driver. “Let no one move. We may tread on it. Keep still.”

For a moment they all obeyed him. He began to crawl through the mud, touching first this, then that, grasping the cushions by mistake, listening for the faintest whisper that might guide him. He tried to light a match, holding the box in his teeth and striking at it with the uninjured hand. At last he succeeded, and the light fell upon the bundle which he was seeking.

It had rolled off the road into the wood a little way, and had fallen across a great rut. So tiny it was that had it fallen lengthways it would have disappeared, and he might never have found it.

“I stole it! I and the idiot — no one was there.” She burst out laughing.

He sat down and laid it on his knee. Then he tried to cleanse the face from the mud and the rain and the tears. His arm, he supposed, was broken, but he could still move it a little, and for the moment he forgot all pain. He was listening — not for a cry, but for the tick of a heart or the slightest tremor of breath.

“Where are you?” called a voice. It was Miss Abbott, against whose carriage they had collided. She had relit one of the lamps, and was picking her way towards him.

“Silence!” he called again, and again they obeyed. He shook the bundle; he breathed into it; he opened his coat and pressed it against him. Then he listened, and heard nothing but the rain and the panting horses, and Harriet, who was somewhere chuckling to herself in the dark.

Miss Abbott approached, and took it gently from him. The face was already chilly, but thanks to Philip it was no longer wet. Nor would it again be wetted by any tear.

Chapter 9

The details of Harriet’s crime were never known. In her illness she spoke more of the inlaid box that she lent to Lilia — lent, not given — than of recent troubles. It was clear that she had gone prepared for an interview with Gino, and finding him out, she had yielded to a grotesque temptation. But how far this was the result of ill-temper, to what extent she had been fortified by her religion, when and how she had met the poor idiot — these questions were never answered, nor did they interest Philip greatly. Detection was certain: they would have been arrested by the police of Florence or Milan, or at the frontier. As it was, they had been stopped in a simpler manner a few miles out of the town.

As yet he could scarcely survey the thing. It was too great. Round the Italian baby who had died in the mud there centred deep passions and high hopes. People had been wicked or wrong in the matter; no one save himself had been trivial. Now the baby had gone, but there remained this vast apparatus of pride and pity and love. For the dead, who seemed to take away so much, really take with them nothing that is ours. The passion they have aroused lives after them, easy to transmute or to transfer, but well-nigh impossible to destroy. And Philip knew that he was still voyaging on the same magnificent, perilous sea, with the sun or the clouds above him, and the tides below.

The course of the moment — that, at all events, was certain. He and no one else must take the news to Gino. It was easy to talk of Harriet’s crime — easy also to blame the negligent Perfetta or Mrs. Herriton at home. Every one had contributed — even Miss Abbott and Irma. If one chose, one might consider the catastrophe composite or the work of fate. But Philip

did not so choose. It was his own fault, due to acknowledged weakness in his own character. Therefore he, and no one else, must take the news of it to Gino.

Nothing prevented him. Miss Abbott was engaged with Harriet, and people had sprung out of the darkness and were conducting them towards some cottage. Philip had only to get into the uninjured carriage and order the driver to return. He was back at Monteriano after a two hours’ absence. Perfetta was in the house now, and greeted him cheerfully. Pain, physical and mental, had made him stupid. It was some time before he realized that she had never missed the child.

Gino was still out. The woman took him to the reception-room, just as she had taken Miss Abbott in the morning, and dusted a circle for him on one of the horsehair chairs. But it was dark now, so she left the guest a little lamp.

“I will be as quick as I can,” she told him. “But there are many streets in Monteriano; he is sometimes difficult to find. I could not find him this morning.”

“Go first to the Caffe Garibaldi,” said Philip, remembering that this was the hour appointed by his friends of yesterday.

He occupied the time he was left alone not in thinking — there was nothing to think about; he simply had to tell a few facts — but in trying to make a sling for his broken arm. The trouble was in the elbow-joint, and as long as he kept this motionless he could go on as usual. But inflammation was beginning, and the slightest jar gave him agony. The sling was not fitted before Gino leapt up the stairs, crying —

“So you are back! How glad I am! We are all waiting— “

Philip had seen too much to be nervous. In low, even tones he told what had happened; and the other, also perfectly calm, heard him to the end. In the silence Perfetta called up that she had forgotten the baby’s evening milk; she must fetch it. When she had gone Gino took up the lamp without a word, and they went into the other room.

The Celestial Omnibus and Other Stories

The Celestial Omnibus and Other Stories Maurice

Maurice The Longest Journey

The Longest Journey Howards End

Howards End A Room with a View

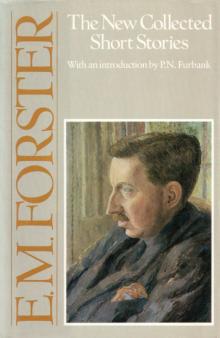

A Room with a View The New Collected Short Stories

The New Collected Short Stories A Passage to India

A Passage to India Where Angels Fear to Tread

Where Angels Fear to Tread Works of E M Forster

Works of E M Forster Selected Stories

Selected Stories The Machine Stops

The Machine Stops Aspects of the Novel

Aspects of the Novel